I've been running 20+ Claude Code agents simultaneously across multiple codebases, orchestrated by a parent agent in my home directory.

It started as an experiment, but it's now how I ship production code across two real codebases — one at Composio (where I work on AI-powered integration workflows), one personal — handling everything from issue triage to PR creation to review comment fixes. On a typical day, a dozen agents are working in parallel, each on a separate git worktree, each with its own tmux session, each completely isolated from the others.

Here's how it works and what I learned building it.

Why Parallel Agents?

The bottleneck in software development isn't writing code — it's context switching. Every GitHub issue requires understanding the codebase, reading related code, figuring out the right approach, implementing, testing, and creating a PR. Even with an AI assistant, that's 20-60 minutes of focused time per issue.

But most of that time, the AI is doing the work while I watch. Why not have it do 15 issues at once?

Claude Code already works autonomously. It reads code, runs tests, creates branches, opens PRs. The missing piece was infrastructure to run many instances in parallel without them stepping on each other.

So I built an orchestrator.

Architecture: Agent Hierarchy

Each agent is a full Claude Code instance running in its own tmux session, attached to its own git worktree. The orchestrator — also a Claude Code instance — manages them all from ~/.

Key constraints:

- Complete isolation: Each agent gets its own working directory, branch, and session. No shared state except the git object store.

- No coordination required: Agents don't know about each other. They work on separate issues on separate branches.

- Stateless orchestrator: The parent agent doesn't maintain a model of what children are doing. It reads live state from the filesystem when asked.

Why tmux Sessions, Not Subagents

Claude Code has a built-in Task tool that spawns subagents — child processes that run autonomously and return a result. It would be the obvious choice for parallelism. I don't use it for this.

Subagents are fire-and-forget. I need human-in-the-loop.

A subagent runs, does its work, and returns a summary. You can't attach to it mid-flight. You can't see what it's doing. You can't course-correct when it's heading in the wrong direction. You can't say "actually, use the existing helper function instead of writing a new one." By the time you see the result, the work is done — right or wrong.

tmux sessions are the opposite. They're persistent, interactive, and observable. At any point I can:

# Peek at what an agent is doing (without interrupting it)

tmux capture-pane -t "relay-3" -p -S -30

# Attach and interact directly

~/claude-relay-session attach relay-3

# Type guidance, then detach (Ctrl-b d) and let it continue

AI agents aren't perfect. They make wrong architectural choices. They misread requirements. They go down rabbit holes. The orchestrator's value isn't just spawning work — it's enabling me to supervise 15 agents the same way I'd supervise 15 junior developers: check in periodically, course-correct when needed, and let them run when they're on track.

The Tab Switching Problem

With 15 active sessions, finding the right terminal tab is its own problem. I don't solve it by memorizing tab positions. I just talk to the orchestrator:

claude: That's relay-44, working on workflow memory monitors. Bash(~/open-iterm-tab relay-44)

The orchestrator scans metadata files, finds the session, and calls an AppleScript helper that searches every iTerm2 window and tab for a matching profile. My terminal switches to the right tab. I'm now looking at the agent's live output. The whole interaction takes seconds.

This turns human-in-the-loop from a bottleneck into a workflow. I don't context-switch between 15 terminal windows trying to remember which is which. I tell the orchestrator what I want to check on, and it puts me there. Check the agent's work, type a correction if needed, detach, move to the next one. A full review pass across all active agents takes minutes, not hours.

The trade-off is real: subagents would be simpler, cheaper (no idle sessions), and fully automated. But I'd lose the ability to intervene, and that intervention is where most of the value comes from. The agents handle the 80% that's straightforward. I handle the 20% that requires judgment. tmux makes that split possible.

Automated Session Monitoring

With 15+ agents running, I kept finding sessions that had finished work 20 minutes ago sitting idle, or stuck waiting for input that never got submitted. The human-in-the-loop approach assumes I'm the one checking — but I can't cycle through 15 tabs every few minutes. I needed automated state tracking.

The key insight: Claude Code already writes structured events to JSONL session files — every user message, assistant response, tool execution, and turn completion. Rather than scraping terminal output to guess what an agent is doing, I watch these files directly. fswatch triggers on file changes; reading the last event tells me whether the agent is active, idle, or done. Event-driven, not polling. Structured data, not regex.

The watcher also auto-fixes a common failure mode where messages sit in the input buffer without being submitted, and writes trigger files when agents finish so the orchestrator knows what needs attention. Three composable scripts, no daemon framework.

The design insight: treat Claude Code's own session files as a structured API instead of scraping the terminal.

Git Worktrees Over Clones

Early on, I used full git clones for each parallel session — ~/secondary_checkouts/relay-1 through relay-9. This worked but was wasteful: each clone duplicated the entire .git/ directory, and operations like git fetch had to run independently in each one.

The session managers now use git worktrees:

# Instead of 10 full clones:

git clone ... ~/secondary_checkouts/relay-1 # ~500MB each

# One repo with lightweight worktrees:

git worktree add ~/.worktrees/relay/relay-1 -b feat/issue-123

Worktrees share the .git/ object store with the main repo. Each one is just a checkout — a few MB instead of hundreds. Git operations are faster because object deduplication happens automatically.

The session manager creates worktrees on demand:

~/claude-relay-session new INT-1234

This finds the next available sequential name, creates a worktree branched off next, symlinks shared resources (.env, .venv, .claude/, CLAUDE.local.md), starts a tmux session, and launches Claude with the ticket context. The whole setup takes under a second.

The Toolbox: ~25 Scripts, No Framework

I didn't build a framework. I built individual scripts that each do one thing, composed through shell conventions. Everything is a bash script in ~/. No Python, no Node, no dependencies beyond tmux, gh, jq, and standard macOS tools (osascript, lsof).

Spawning

| Script | Purpose |

|---|---|

claude-batch-spawn |

Spawn N sessions for N issues in one command |

claude-spawn |

Spawn single session in new terminal tab |

claude-spawn-with-prompt |

Spawn with inline prompt argument |

claude-spawn-with-context |

Spawn with custom prompt from file |

The batch spawner is what I use most:

# Check what's running

~/claude-status

# Spawn 5 agents for 5 GitHub issues

~/claude-batch-spawn splitly 299 300 301 302 303

Each agent gets an initial prompt: fetch the issue, create a branch, read the codebase, implement the fix, run tests, create a PR. Then I walk away.

Monitoring

The dashboard is the single most important script. (There's a live example of the full dashboard later in this post.)

~/claude-status

It shows every active session with:

- Live git branch (read directly from the worktree)

- Claude's auto-generated summary (extracted from Claude's internal session JSONL)

- Activity age (how recently the session wrote to its file)

- Session ID (for

claude -rresume)

The clever part: it doesn't rely on agents reporting their status. It introspects Claude's own data. The script follows the chain: tmux session → pane TTY → Claude PID → working directory → Claude's session file. This means the dashboard is always accurate even if an agent forgets to update its metadata.

# The path transformation that makes it work:

# /Users/user/.worktrees/relay/relay-3 -> -Users-user-.worktrees-relay-relay-3

PROJECT_PATH=$(echo "$CWD" | tr '/_' '--')

PROJECT_DIR="$HOME/.claude/projects/$PROJECT_PATH"

Lifecycle

~/claude-relay-session new INT-1234 # Create

~/claude-relay-session ls # List all

~/claude-relay-session attach int-3 # Attach to watch/interact

~/claude-relay-session cleanup # Kill completed (PR merged)

~/claude-relay-session kill int-3 # Kill specific

Cleanup is automatic — it checks if the PR is merged before killing a session and removing the worktree.

Automation

~/claude-review-check relay # Find PRs with review comments, send fix prompts

~/claude-bugbot-fix relay # Find Cursor BugBot comments, send fix prompts

~/claude-watch-session relay-3 # Monitor a single session's state (active/idle/stuck)

~/claude-watch-all # Start watchers for all active sessions

~/claude-poll-sessions # Read trigger files for orchestrator notifications

~/claude-pr-dashboard-html # Generate HTML version of PR dashboard

~/claude-open-all splitly # Open terminal tabs for all sessions

claude-review-check is particularly useful. It scans all sessions that have PRs, checks for CHANGES_REQUESTED review decisions or unresolved inline comments via the GitHub API, and sends a prompt to the tmux session telling the agent to fix the issues. The agent reads the comments, makes fixes, pushes, and replies — all without me touching anything.

The Session Lifecycle

Steps 3-8 happen autonomously. Steps 10-11 require me to run one command. The rest is standard code review.

How Autonomous Are the Agents, Really?

This is the part that surprises people. These aren't toy demos generating hello-world PRs. Each agent operates with the full toolkit of a senior developer — and uses most of it without asking.

The Toolchain

Development workflow — GitHub, Linear, and Slack form the core loop. Agents create branches, open PRs with structured descriptions (Why/What/How to Test), enable auto-merge, fetch review comments, push fixes, and resolve threads — all via the gh CLI and GraphQL API. After a PR is ready, they create Linear tickets (with priority, assignee, and PR links pre-filled from cached IDs in CLAUDE.local.md) and draft Slack announcements for #engineering-pr-review. Slack is one of the hard permission boundaries — agents must ask before posting. Before any PR goes up, agents run /codex-review-loop: an automated review that generates a patch, submits it to Codex for analysis (bugs, security, types, error handling), and iteratively fixes issues until it passes.

Observability and debugging — Agents query Datadog logs, pull LLM Obs trace links for PR descriptions, and verify staging deployments. Large log responses go through a workbench pattern (sync_response_to_workbench=true) that processes results server-side — a 100k token log dump would blow the context window, so Composio filters and summarizes before the agent sees it. For deeper debugging, agents can request AWS access. I manually approve, and they get a Terraform-managed IAM role via their own SSO session — read-only access to RDS, ECS, S3, CloudWatch, 1-hour credential expiry, isolated and auditable per session.

Infrastructure and testing — Agents trigger end-to-end workflow runs against the staging API, wait for completion with timeout scripts, and capture evidence for PR descriptions. Terraform changes go through a PR-based workflow: agents make changes, automated plans run on push, and they comment /apply-staging to apply. They never run terraform apply directly.

All external integrations — Linear, Slack, Datadog, AWS — are powered by Rube, Composio's MCP server, which gives Claude Code native access to 800+ apps through a single connection:

claude mcp add rube --transport http https://rube.app/mcp

Without a unified tool layer, each agent would need its own API keys, OAuth tokens, and client setup for every service. Composio handles auth, rate limiting, and schema management — the agents just call tools.

Working on Composio and simultaneously being a heavy user of it has given me a strong opinion: the tool layer is the most underinvested part of the AI agent stack. Everyone focuses on model capabilities, prompt engineering, and orchestration frameworks. But the thing that actually determines whether an agent can do useful work is whether it can interact with the systems where work happens — your issue tracker, your communication tool, your CI pipeline, your cloud provider.

An agent that can write perfect code but can't create a Linear ticket, post to Slack, or check Datadog logs is an agent that still needs a human for everything except typing. The tool layer is what turns an AI coding assistant into an AI coworker. Every integration compounds: an agent that can create a PR and create a ticket and post to Slack and enable auto-merge does the work of four manual steps in one autonomous flow.

Building tools for agents is also different from building APIs for humans. Agents need self-describing schemas (or they'll guess wrong and waste tokens retrying), compact responses (or they'll blow the context window), and auth that just works (no interactive OAuth prompts, no browser redirects). Every friction point that a human can work around becomes a failure mode for an agent.

What Requires Permission

Not everything is autonomous. The hard boundaries:

- AWS / database access — Agents request access when they need to debug production. I approve, and they get a time-limited read-only SSO session. No ambient credentials.

- Slack messages — Must ask before posting. Agents draft the message and wait for approval.

- Protected branches — Cannot push to

nextormaster. Must create PRs. - Terraform apply to prod — Happens automatically on merge, but the merge itself requires human approval.

Everything else — reading code, writing code, running tests, querying databases, creating PRs, responding to review comments, creating tickets — happens without me touching anything. A typical agent will go from "here's a Linear ticket" to "PR is open, Codex review passed, auto-merge enabled, Linear ticket created, Slack draft ready for your approval" completely on its own.

Self-Polling Loops

All of the above is about single-shot autonomy — an agent receives a task, executes it, and stops. The next evolution was closing the feedback loop entirely.

Agents now run autonomous iteration cycles when fixing PRs. Instead of the old pattern — fix the issue, push, stop, wait for me to check CI and relay the results — they follow a codified loop:

fix → push → wait 5 minutes → poll CI status → check for new review comments → if anything failed or new feedback appeared, fix again → repeat until green → enable auto-merge → notify the orchestrator.

I dispatch "fix CI on PR #1121" and the agent handles the entire fix-poll-iterate cycle independently. It only pings back when the PR is genuinely ready to merge. No more "CI failed again, go fix it" back-and-forth that used to eat up half my orchestrator interactions.

The loop lives in CLAUDE.local.md, so every session follows it by default — I don't include polling instructions in each prompt. Combined with the session watchers that detect stuck states, this means an agent can go from "received task" to "PR merged" without any human interaction at all, as long as nothing requires judgment. When it does, the watcher flags it, the orchestrator routes my attention there, and I intervene on just the part that needs me.

This is where the system starts feeling less like "running 20 terminals" and more like managing a team. Most of the time, they're fine on their own. I just handle the exceptions.

Prompt Architecture: CLAUDE.md Layers

Each agent loads instructions from a layered system of markdown files:

The CLAUDE.local.md in each project is extensive — 500+ lines covering:

- Cost efficiency rules: "Tool results stay in context → exponential cache costs. Target: $2-5 per PR."

- Debugging guides: How to query production databases, parse agent event files from S3, check Datadog traces

- Workflow conventions: Two-PR pattern for database migrations, Terraform apply-via-PR-comment, staging verification

- Communication style: "Write like a human talking to coworkers, not a robot generating a report. Keep it short."

- Safety rails: "NEVER push directly to

next. ALWAYS ask for user permission before posting to Slack."

These files are symlinked from the main repo into each worktree, so every agent gets identical instructions.

The home directory has its own CLAUDE.local.md — the orchestrator instructions. It describes the agent hierarchy, all available scripts, common workflows, and tips like "peek at sessions without attaching using tmux capture-pane."

Communication: tmux as Message Bus

Agents don't have an API. They're interactive CLI processes. Communication happens through tmux:

# Send a message to a running agent

tmux send-keys -t "relay-3" "Please check the PR review comments and address them" Enter

# For multi-line prompts (avoids shell escaping nightmares)

tmux load-buffer /tmp/prompt.txt

tmux paste-buffer -t "relay-3"

sleep 0.3

tmux send-keys -t "relay-3" Enter

This is crude but effective. The agent sees the message as if a human typed it. No custom protocols, no IPC — just terminal I/O.

The paste-buffer + separate Enter pattern was learned the hard way. tmux paste-buffer consumes the trailing newline, so the prompt sits in the input buffer without being submitted unless you explicitly send Enter afterward.

AppleScript: The Glue Between Agents and My Attention

The most underappreciated part of the system isn't about AI at all — it's about directing human attention. With 15 agents running, the hardest problem isn't getting them to work. It's knowing which one needs me right now and getting there instantly.

Agent-Initiated Notifications

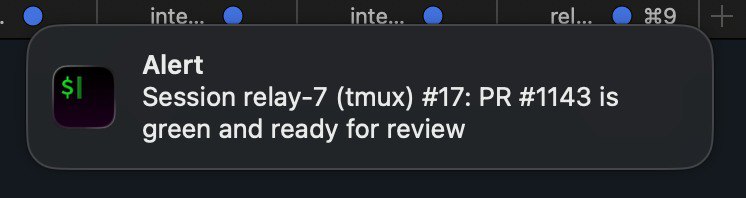

Any agent can request my attention:

~/notify-session "PR comments addressed, ready for review"

It's a tiny script — three lines of functional code. It uses iTerm2's native OSC 9 escape sequence:

printf '\033]9;%s: %s\007' "$SESSION_NAME" "$MESSAGE"

The notification appears as a native macOS notification:

The key detail: clicking it navigates directly to that agent's terminal tab. Not to iTerm2 generally — to the exact tab where the agent is running. No searching through 15 tabs to find who pinged me.

Agents call this when they finish a PR, when they're blocked and need a decision, or when they hit a permission boundary (like needing Slack approval). It's their way of saying "I need you" without me polling.

Tab Navigation by PR Link

The orchestrator can navigate me to any agent using just a PR link. When I say "take me to the session working on PR #1121", it:

- Scans metadata files in

~/.relay-sessions/for matching PR URLs - Finds the session name (e.g.,

relay-44) - Calls

~/open-iterm-tab relay-44

The tab opener uses AppleScript to search every iTerm2 window and tab for a matching profile name:

tell application "iTerm2"

repeat with aWindow in windows

repeat with aTab in tabs of aWindow

repeat with aSession in sessions of aTab

if profile name of aSession is equal to "relay-44" then

select aWindow

select aTab

return "EXISTING"

end if

end repeat

end repeat

end repeat

end tell

If the tab already exists, it switches to it. If not, it creates a new tab and attaches to the tmux session. Each tab's profile name is set to the session name at creation, so this lookup is reliable.

This means I can go from "this PR has a failing CI check" to "I'm looking at the agent's terminal" in one sentence to the orchestrator. No mental mapping of PR numbers to session names to tab positions.

Batch Tab Management

~/claude-open-all relay # Open tabs in current window

~/claude-open-all --new-window splitly # Open in a fresh window

This iterates through all active tmux sessions, calls open-iterm-tab for each, and deduplicates — if a tab for relay-44 already exists, it skips it instead of creating a duplicate.

The result: one iTerm2 window with a tab per active agent, each named after its session. I can Cmd-1 through Cmd-9 to jump between them, or use iTerm's tab search to find one by name.

AppleScript handles the full tab lifecycle — not just opening. When a session is killed (PR merged, cleanup runs), the kill command uses AppleScript to find and close the corresponding iTerm tab before destroying the tmux session. This matters because once tmux dies, the tab name changes and becomes unfindable. So the cleanup sequence is: close iTerm tab → kill tmux session → remove git worktree. Everything gets cleaned up, no orphan tabs left behind.

The Attention Loop

Putting it all together, the attention flow looks like this:

- Agents work autonomously

- Agent finishes / gets stuck → calls

~/notify-session - Notification appears → I click it → lands in the right tab

- I review, course-correct if needed, detach

- Or: I ask orchestrator "what needs my attention?" → it checks dashboards → navigates me to the right tab

The system never makes me remember which tab is which, which session is working on which PR, or where to find the agent that just finished. All that routing is automated. My job is just to make decisions when they're needed.

Metadata: Two Layers of State

Each session has two sources of truth:

1. Manual metadata (~/.relay-sessions/relay-3):

branch=feat/INT-1234-fix-auth

pr=https://github.com/acme-corp/relay/pull/987

issue=https://linear.app/acme-corp/issue/INT-1234/fix-auth

summary=Fix OAuth token refresh in Slack integration

status=PR created, waiting for review

Written by agents via ~/claude-relay-session update. Can become stale.

2. Live Claude data (~/.claude/projects/--Users--user--relay/):

Auto-generated session JSONL with conversation history and summaries. Always current.

The dashboard prefers live data. If metadata branch disagrees with the actual git branch, it shows (meta: feat/old-branch) as a warning. This dual-layer approach means I get accurate information even when agents don't update their metadata.

Cost Control

AI agents running in parallel can burn money fast. I set explicit cost targets in the agent instructions:

Tool results stay in context → exponential cache costs. Target: $2-5 per PR.

Specific rules:

- Use the Task tool for exploration — subagent reads 20 files, only the summary enters the main context

- Read files once — remember content, never re-read

- Don't retry failures — if something fails twice, change approach

- Filter everything —

--jq,head_limit,--oneline - Batch commits — one commit, not five

- No

--watch— single checks only

The difference is real. An undisciplined agent can spend $15-30 on a simple PR by re-reading files, retrying failing commands, and accumulating massive context. With these rules, most PRs land at $2-5.

The Orchestrator Agent Itself

The parent agent — the one sitting in ~/ — is also a Claude Code instance. It reads CLAUDE.local.md from the home directory, which describes the entire system: all scripts, all workflows, the agent hierarchy, tips and gotchas.

This means I can tell the orchestrator: "spawn agents for all open GitHub issues that aren't already being worked on" and it will:

- Run

gh issue listto get open issues - Run

~/claude-statusto see what's already in progress - Run

~/claude-batch-spawn splitly <remaining issues> - Open terminal tabs with

~/claude-open-all splitly

Or: "check all relay PRs for review comments and have agents address them" — one command, and every agent with pending feedback gets a prompt to fix it.

The orchestrator doesn't do any coding itself. It manages. It's a manager agent whose direct reports are coding agents, and its tools are shell scripts.

The PR Dashboard

With 15+ PRs open at any given time, I need to know where things stand. The orchestrator runs claude-pr-dashboard, which constructs a single batched GraphQL query to pull status for every open PR across both projects:

~/claude-pr-dashboard

It returns review decisions, CI status, unresolved comment threads, and merge readiness — all in one shot. No N+1 API calls. Here's what a real dashboard looks like with 11 active sessions:

But the real value isn't just visibility. The orchestrator can analyze the dashboard and recommend what to focus on. "These 3 PRs just need one more review comment addressed. These 2 are green and ready to merge. This one has been stuck on CI for an hour — want me to check what's failing?" It triages the work across all active sessions and tells me where my attention has the highest leverage.

The Orchestrator as My Planning Agent

Over time, something unexpected happened: the orchestrator became my primary interface for thinking about work — not just executing it.

It started with simple triage. "What should I focus on right now?" The orchestrator checks the PR dashboard, finds which PRs are closest to merge (green CI, no unresolved comments), which sessions are stuck (no activity in hours), and which tickets have no session yet. It tells me where my attention has the highest leverage.

But it grew beyond that. Now I use it to:

Assess current workload — "What am I working on across both projects?" It pulls live data from all sessions, all open PRs, all Linear tickets, and gives me a single coherent picture. Before this, I had to check GitHub, check Linear, check tmux sessions — three different dashboards, three different contexts. Now it's one question.

Identify high-impact work — "What are the most impactful things we could be doing that we're not?" It can cross-reference open tickets, recent bugs, team priorities, and suggest what to spawn next. It has the context of the full codebase (via the child agents' CLAUDE.md files) and the project management state (via Linear), so its suggestions are grounded in reality.

Plan implementation strategy — For complex features, I'll talk through the approach with the orchestrator before spawning any agents. "This feature touches the database schema, the API layer, and the frontend. Should we split it into multiple tickets?" The orchestrator doesn't have project context itself (it lives in ~/), so it spawns a subagent inside the project directory that loads the project's CLAUDE.md and AGENTS.md, explores the codebase structure, and reports back. The orchestrator then uses that understanding to decide how to decompose the work across multiple tmux sessions. It's planning with real codebase knowledge, not guessing.

Track progress without context-switching — Mid-afternoon, I'll ask "how are things going?" and get a summary: 3 PRs merged since morning, 2 waiting on review, 1 stuck on a failing test (agent has retried twice, might need guidance), 4 still in progress. All without opening a single browser tab.

This wasn't the plan. I built the orchestrator to spawn and manage sessions. But because it has access to everything — the dashboard scripts, the GitHub API, Linear via MCP, the live session data — it naturally became the place where I think about work at a higher level. The terminal tab where the orchestrator runs is now the first thing I open in the morning and the last thing I check before I'm done for the day.

Numbers

What Worked

Git worktrees are the right abstraction. Complete branch isolation with shared objects. Fast creation and deletion. No sync issues between clones.

tmux as session runtime. Dead simple, rock-solid, observable. tmux capture-pane lets me peek at any agent without interrupting it. Sessions survive terminal crashes. Named sessions make everything addressable.

Live data extraction over self-reporting. Agents are unreliable narrators. Reading Claude's actual session files is more accurate than asking agents to update metadata.

Bash scripts over frameworks. Each script is 60-220 lines, does one thing, composes with others. No dependency management, no build step, no abstraction layers. When something breaks, I read the script and fix it.

Batch GraphQL for PR monitoring. claude-pr-dashboard constructs a single GraphQL query for all open PRs instead of N+1 REST calls. Efficient and fast, even with 15+ open PRs.

Layered CLAUDE.md files. CLAUDE.md (committed, minimal) + AGENTS.md (committed, conventions) + CLAUDE.local.md (gitignored, everything else). Different audiences, different lifespans, clean separation.

Cost rules in agent instructions. Explicit budgets combined with concrete rules — $2-5 per PR, use subagents for exploration, filter all output, never re-read files — changed agent behavior immediately. The budget sets the tone; the rules give it teeth.

What Didn't Work

Full git clones for parallelism. My first approach: 10 complete clones of the repo. 5GB+ of disk per project, slow fetches, occasional .git/ corruption. The session managers now use worktrees, though some older scripts (like claude-batch-spawn) still reference the legacy clones. The migration is ongoing.

Relying on agents to update metadata. Agents frequently forget to call ~/claude-relay-session update. The JSONL-based monitoring system was built specifically to compensate for this — reading Claude Code's own session files for ground-truth state instead of trusting agents to self-report. If I'd relied purely on self-reported metadata, the dashboard would be perpetually stale.

Long tmux send-keys strings. Shell escaping in tmux is brutal. Characters like #, *, {} get mangled by zsh before tmux sees them. I switched to file-based prompts (load-buffer + paste-buffer) for anything beyond a simple sentence.

Complex approval workflows. I initially tried multi-step approval gates for dangerous operations. Too much friction. I simplified to: agents can't push to protected branches or post to Slack without explicit permission. Binary gates, not workflows.

osascript for terminal automation. AppleScript's keystroke command truncates strings around 80 characters. I spent an embarrassing amount of time debugging why long commands were getting cut off. The fix: send commands in separate osascript calls, or use shorter strings.

Duplicate detection in batch-spawn. I spawned duplicate agents for the same issue more than once before adding detection. An embarrassing waste of compute that was entirely avoidable.

The remaining rough edge is review-check triggers — claude-review-check still runs when I remember to run it. A cron job or webhook would close that loop. But honestly, the current system already handles 80% of my workflow: batch-spawn issues, let agents work, check the dashboard, trigger review fixes, cleanup merged PRs.

Claude Code Now Has Native Agent Teams

Here's the twist: while I was building all of this, Claude Code shipped native agent teams — a built-in system for coordinating multiple Claude Code instances. And it's not just simple subagent parallelism. It's genuinely impressive:

- Team lead + teammates model — a lead session spawns and coordinates workers, with delegate mode restricting the lead to coordination only (exactly how my orchestrator works)

- Shared task lists — agents create, claim, and complete tasks with dependency tracking

- Inter-agent messaging — teammates communicate directly, not just report back to the lead

- Split-pane tmux display — all agents visible side by side

- Plan approval gates — teammates plan before implementing, lead reviews the approach

- Mid-flight intervention — you can interact with any teammate session directly

This goes well beyond fire-and-forget subagents. The patterns I arrived at empirically — team lead orchestration, task-based coordination, tmux as the display layer, plan-before-implement gates — are all there in the native implementation.

So why does my custom system still exist? Different use case.

Persistence. Native teams live within a single session. When the lead exits, the team is done. My tmux sessions persist for days or weeks — an agent can work on a PR Monday, get review comments Tuesday, and address them Wednesday, all in the same session. Native teams have a known limitation around session resumption: teammates can't be resumed once disconnected.

External workflow integration. My system doesn't just coordinate agents — it integrates them into the full development lifecycle. Batch-spawning from GitHub issues and Linear tickets. The PR dashboard that queries every open PR via batched GraphQL. claude-review-check that automatically sends fix prompts when reviewers leave comments. claude-bugbot-fix that bridges Cursor's BugBot with Claude agents. Automated cleanup when PRs merge. None of this is about agent-to-agent coordination — it's about agent-to-workflow coordination.

Scale pattern. Native teams are one team per session — a lead coordinating a handful of teammates on related tasks. My system runs 15+ independent long-lived sessions across multiple projects simultaneously, each on its own git worktree, each with its own issue context. It's not one team doing one thing — it's many independent agents doing many unrelated things, with a dashboard and attention-routing layer on top.

Maturity. Native agent teams are still experimental and disabled by default. The feature is evolving fast, but for production workflows I need reliability today.

I expect to adopt native teams for intra-session coordination as the feature stabilizes — especially the task list and inter-agent messaging, which I currently hack through tmux send-keys. But the infrastructure layer (worktrees, dashboards, issue tracking, attention routing, persistence) will stay custom. That's the glue between "AI agents working together" and "AI agents integrated into my actual development workflow."

Why Fully Autonomous Doesn't Work

There's a seductive vision in the AI agent space: fully autonomous systems that take a task description and ship production code without human involvement. Just describe what you want, walk away, come back to a merged PR.

We keep seeing this attempted, and it keeps falling short.

Anthropic's C Compiler — 16 Claude instances, 100K lines of Rust, ~2,000 sessions, $20K in API costs.

- Compiled Linux 6.9, passed 99% of GCC torture tests, ran Doom

- But issue #1: hello world doesn't compile — broken include paths for

stddef.handstdarg.h - A basic usability problem any human catches in five minutes

- Worth noting: a C compiler is a near-ideal agent task — decades-old spec, comprehensive test suites, known reference compiler. Most real projects have none of these advantages.

Cursor's Web Browser — Hundreds of GPT-5.2 agents for a week, 3M lines of Rust, "built a browser from scratch."

- Generated a massive codebase, made headlines

- Barely compiles, CI failing on main, pages take ~1 minute to render

- Leans heavily on Servo and QuickJS despite "from scratch" claims

- 3M lines is bloated — Ladybird and Servo do more in ~1M each

- Flat agent coordination failed completely (risk-averse, held locks, churned). Had to introduce planner/worker hierarchy. Their Solid→React migration (+266K/-193K edits) "still needs careful review" after three weeks.

The pattern is consistent: fully autonomous agents produce something, but the gap between something and production-quality code that your team can maintain is exactly where human judgment lives.

My orchestrator system is built on the opposite premise. Instead of trying to remove humans from the loop, it optimizes the loop itself. The question isn't "how do we make agents work without humans?" — it's "how do we make human oversight of 20 parallel agents as efficient as possible?"

That's what the entire infrastructure exists to solve:

- tmux sessions — so I can attach, guide, and detach in seconds

- AppleScript tab management — so I never waste time finding the right agent

- Notifications — so agents tell me when they need me instead of me polling

- The PR dashboard — so I know exactly where my attention has the highest leverage

- The orchestrator itself — so I can make decisions in natural language and have them routed to the right place

The result is a system where agents handle the 80% that's mechanical — reading code, writing implementations, running tests, creating PRs — and humans handle the 20% that requires judgment — architecture decisions, priority calls, edge case handling, "actually, don't do it that way."

That 80/20 split, with good infrastructure to make the human side efficient, is more productive than either fully manual development or fully autonomous agents. And I think it will stay that way for a while.

Takeaways

Parallel AI agents are a multiplier, not a replacement. I still review every PR. I still make architectural decisions. But instead of implementing one thing at a time, I make decisions in batches while agents handle the implementation.

Infrastructure matters more than prompts. Getting the isolation right (worktrees), the observability right (live data extraction), and the lifecycle right (spawn/monitor/cleanup) was harder and more valuable than prompt engineering.

Bash is fine. The entire orchestration layer is 2,000 lines of bash. No framework, no abstraction, no dependencies. When something breaks, I read 200 lines of shell script and fix it in minutes. The right level of sophistication for glue code is the lowest level that works.

Cost discipline requires explicit rules. Telling agents "be efficient" does nothing. Telling them "$2-5 per PR, use Task tool for exploration, filter all output, never re-read files" changes behavior immediately.

The filesystem is the best database for single-user systems. Session metadata in flat files, agent instructions in markdown, state derived from the process tree. No database to manage, no schema to migrate, everything is cat-able and grep-able.

This blog post — and the platform serving it — was built and deployed by another AI agent system I run. That one handles personal life infrastructure instead of code: finances, memory, email processing, web publishing. I wrote about it here.